Some technical stuff about light and vision

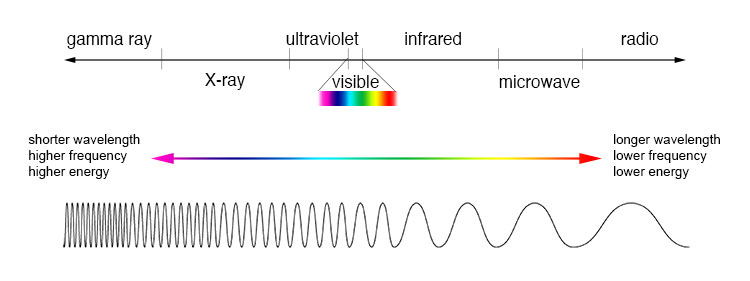

Color is the human eye's response to electro-magnetic (EM) radiation in the bandwidth between about 400 and 700 nanometers (nm), a relatively small part of the entire EM spectrum from radio waves, micro-waves, infrared (heat), light, ultra-violet, X-rays, up to gamma rays.

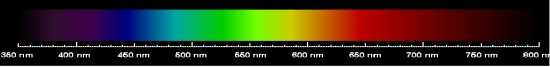

The image below is, I believe, a photo of the spectrum of white light, probably generated with the help of a prism, calibrated with the wave lengths in nanometers. As you can see, it's a matter of opinion where the visible range starts and finishes.

Most of our experience of color comes from reflected light: sunlight shining on the countryside, pictures in a book or magazine illuminated by the overhead lights. The meat in the butcher's display cabinet is illuminated by a warm colored flourescent tube to enhance the redness of the meat. Some of our experience comes from direct light: the familiar traffic lights, lights on the Christmas tree and of course the TV and computer screen. This difference between reflected light and direct light is critical to our understanding of the process and the results of mixing colors, but as the color enters our eye as a mixture of wavelengths, the source, (reflected or direct) is irrelevant.

We humans, like all mammals and, to a certain extent other members of the animal kingdom (although most of the

remainder of this discussion relates to the human perception of color), perceive color through cells in

the retina at the back of the eye called "cones", named after their general shape. The retina also

has "rod" cells that perceive light and dark but, as the rods are not involved in color perception, this is that

last I'll be referring to them.

The cone cells come in three types, being sensitive to a narrow band of wavelengths that are generally identified as

blue (420 nm), green (534 nm) and red (564 nm). The process of getting the color signals to the brain is another

long and fascinating story, which I will touch on later.